Ukrainian Children in the Russian Federation’s Register of Terrorists and Extremists

Under Vladimir Putin’s rule, the Russian Federation (hereinafter – Russia or the RF) has transformed into an authoritarian, and later overtly totalitarian state, founded on control, repression, and intimidation. This model is being actively extended to the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine (hereinafter – TOT), where Russia has set up its own security apparatus, often involving local collaborators. Particular pressure is placed on Ukrainian citizens who remain in the TOT. The occupation authorities seek to fully integrate them into Russia’s legal, political, and ideological space by means of coercion and fear. One key method is forced passportisation: without a Russian passport, residents are denied access to healthcare, social benefits, and even education. While school attendance is mandatory, pupils cannot receive official documentation without holding a Russian passport. This creates a coercive, self-perpetuating system. Any signs of dissent or disobedience lead to criminal or administrative penalties. Residents have been prosecuted for displaying Ukrainian symbols, posting on social media, or refusing to participate in pro-Russian events, often under charges related to “extremism” or “terrorism”. As a result, Russian authorities now routinely place people in the Register of Terrorists and Extremists, which has effectively become a list of political dissenters. By the end of July 2025, at least 816 Ukrainian citizens had been added to this register, most of them after the start of the full-scale invasion. The number is rising rapidly, which is a cause for serious concern.

What is the “Register of Terrorists and Extremists”?

The Register of Terrorists and Extremists (hereinafter – the Register) was established in 2001 in accordance with Article 6 of the Federal Law of 7 August 2001 No. 115-FZ “On Countering the Legalisation (Laundering) of Proceeds from Crime and the Financing of Terrorism”. It is maintained by the Federal Financial Monitoring Service (Rosfinmonitoring), which operates under the “Rules for determining the list of organisations and individuals for whom there is information about their involvement in extremist activity or terrorism, and for communicating this list to organisations conducting transactions with funds or other property, as well as to individual entrepreneurs”, approved by Resolution No. 804 of the Government of the Russian Federation of 6 August 2015.

The Register includes both legal entities and individuals for whom there is information indicating involvement in terrorist or extremist activities.

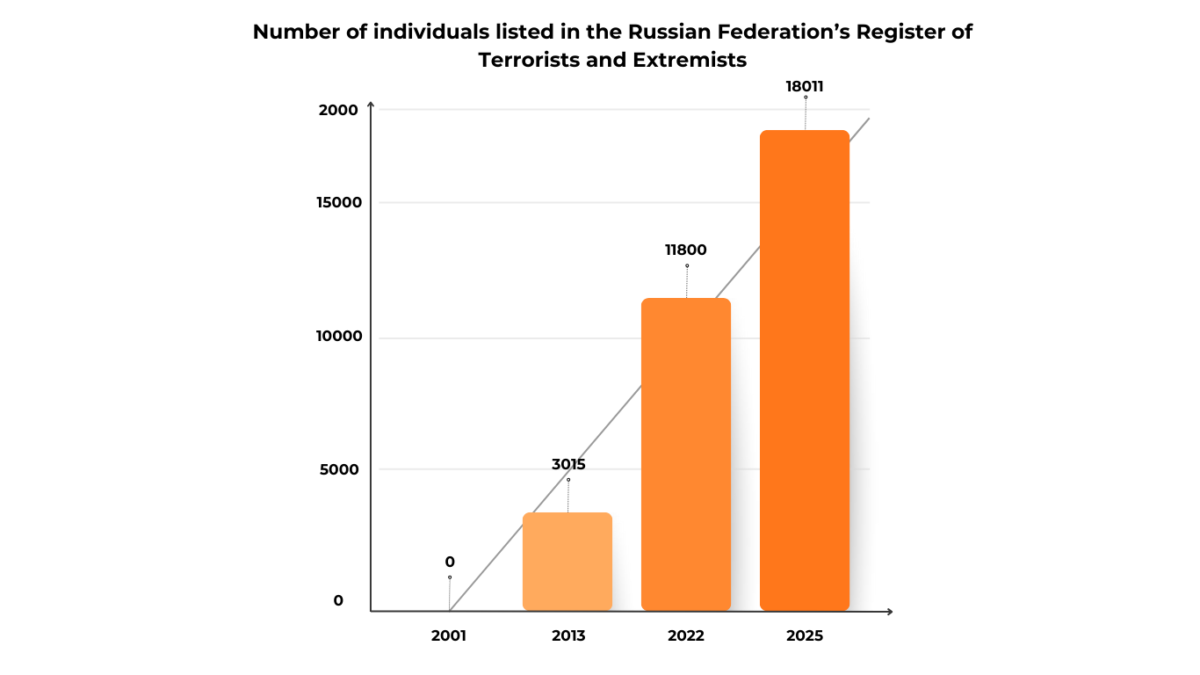

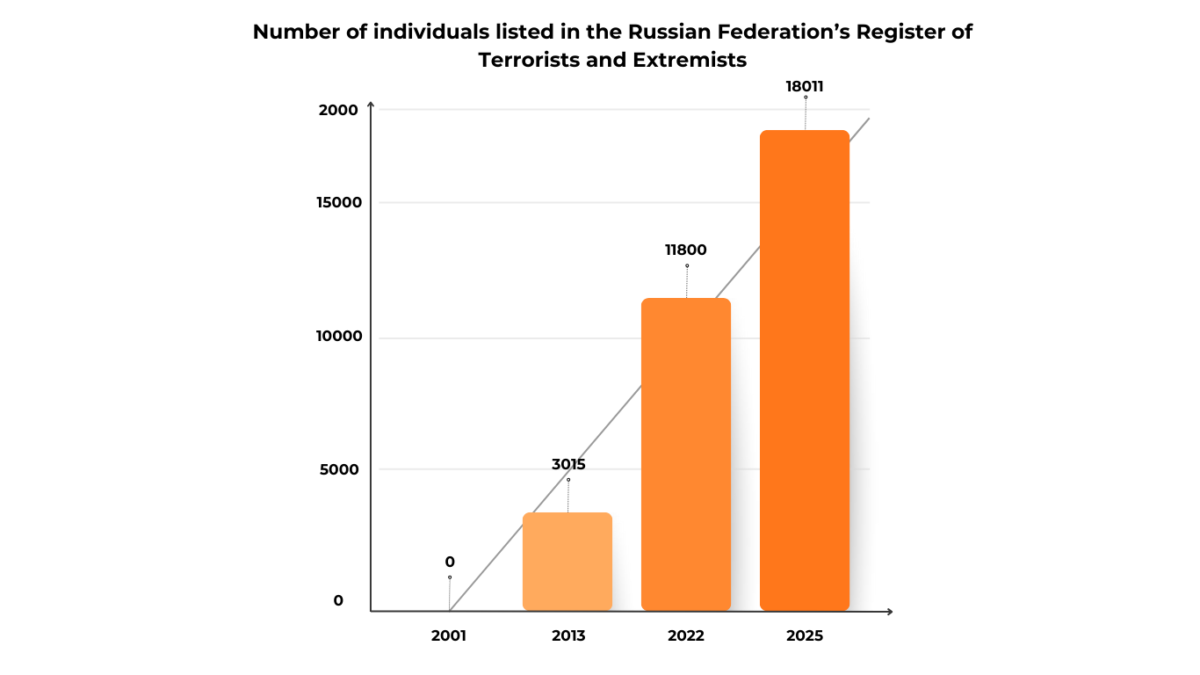

Over the 12 years of the Register’s existence prior to the start of Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine (as of October 2013), it included 3,015 individuals, among them 7 Ukrainian citizens. At the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, the Register already listed 11,800 individuals, including 132 Ukrainians. As of July 2025, the number had increased to 18,011, with 816 of them being Ukrainian citizens.

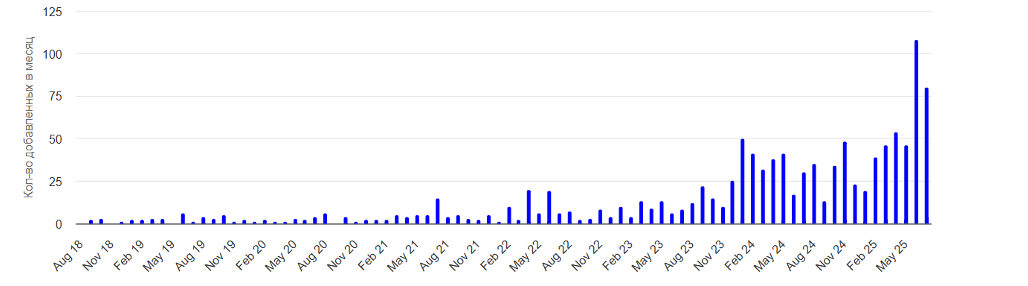

June 2025 saw a record number of new “terrorists” added to the list – 285 individuals were designated as linked to terrorism. The previous record was set in November 2024, with 272 additions. This sharp increase is due to the inclusion of Ukrainian nationals.

Number of Ukrainian nationals added to the Register

It is worth noting not only the sharp increase in the number of individuals added to the Register but also the alarming trend of decreasing age – in 2025, according to Rosfinmonitoring data, the youngest “terrorist” was just 14 years old. This practice points to a deliberate Russian policy of criminalising minors for dissent, protest behaviour, or simply holding pro-Ukrainian views.

Among the 150 minors included in the Register, 13 are Ukrainian nationals (aged 18 or younger).

- Donetsk region (Donetsk, Mariupol, Makiivka, Krasnoarmiisk) – aged 16 to 18

- Luhansk region (Luhansk) – aged 17

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Simeiz, Yalta, Simferopol) – aged 17 to 18

- Kherson region (Tsiurupynsk, Chaplynka) – aged 16 to 18

- Odesa region (Odesa) – aged 15

This once again highlights the deliberate use of this tool as an element of the occupation policy.

Grounds and Consequences of Inclusion in the Register

In Russia, a person, including a minor, can be labelled a “terrorist” or “extremist” without even a court conviction. It is enough for them to be officially recognised as a suspect or accused of an offence under so-called “extremist” articles.

A person is added to the Register based on a notification sent by any of the following bodies:

- The Office of the Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation or the prosecutors of its constituent entities

- The Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation

- The Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation or its regional branches

- The Federal Security Service (FSB)

- The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation or its regional departments.

In addition to the usual articles, such as Article 282.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (organisation of an extremist community) or Article 205.2 (justification of terrorism), from 1 June 2025 the Register may also include those whose actions are classified by investigators or the court as motivated by “political, ideological, racial, national or religious hatred or enmity” or by “hostility towards a particular social group”.

Articles frequently used for such persecution include:

- Spreading “false information” about the use of the Russian Armed Forces (paragraph “d” of part 2 and part 3 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation)

- Repeated “discrediting” of the Russian Armed Forces (Article 280.3)

- “Violating the territorial integrity” of Russia (Article 280.2)

- Multiple instances of promoting or displaying banned symbols (Article 282.4)

- Calls for actions that “threaten state security” (paragraph “d” of part 2 and part 3 of Article 280.4)

- “Hooliganism” motivated by extremism (Article 213) and similar offences.

All these articles are increasingly used not to counter genuine threats, but as a convenient pretext for repressing citizens who express pro-Ukrainian views or criticise the actions of the Russian authorities.

Since 2013, being added to the Register has automatically brought a series of severe restrictions: bank accounts are frozen, inheritance is denied, and all financial transactions are prohibited.

However, the most damaging effects are not only legal but also social. The label of “terrorist” or “extremist” becomes a stigma that leads to isolation from society: employers refuse to hire, and educational institutions deny admission or continuation of studies. According to those already listed on the Register, this status amounts to being effectively erased from public life: “The Rosfinmonitoring list [the Register] is a civil death. No one will employ you. Even relatives are refused opportunities because of it. The same goes for education”.

What Are Children Guilty Of?

Very little information from open sources is available on why children are added to the Register of Terrorists and Extremists. Parents and relatives of minors rarely speak publicly about such cases – out of fear of persecution and a wish not to make the situation worse. This is understandable, as placing a child on the Register effectively destroys their normal life and puts their future at risk.By contrast, Russian law enforcement agencies regularly report on the “successful prevention of crimes” among minors, often with sensational coverage in the media. For example, in October 2024 the FSB, together with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Investigative Committee, carried out a large-scale operation in 78 regions of Russia. As part of this campaign, operational and “preventive” measures were taken against 252 people allegedly involved in “destructive” online communities – 156 of them were minors. As a result, 39 people aged between 14 and 35 were detained and labelled as “radicals”.

Among those detained was a minor from temporarily occupied Crimea, accused of preparing a terrorist attack because he had drawn pictures of weapons in pencil in his school exercise book. After a search of his home, the teenager was taken to the “FSB Directorate for the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol”. Propaganda Telegram channels showed a video of him as an example of a “successful special operation”. What happened to the boy afterwards remains unknown, as does whether he was added to the Register.

A similar incident occurred in April 2025 in the TOT of Donetsk region. The so-called “FSB of the DPR” reported the detention of a pupil from School No. 14, accused of preparing an explosion at the school and of supporting the “Columbine” movement, which is classified as terrorist in Russia. The teenager’s fate is also unknown.

Unlike in the TOT, in Russia itself some cases become public thanks to the efforts of relatives, offering a glimpse into the typical pattern of such cases.

The case of 15-year-old Arseniy Turbin, a ninth-grade pupil from Russia, was widely covered by independent media. In June 2024 he was sentenced to five years in prison for distributing leaflets criticising Putin. During a compulsory psychiatric examination, doctors claimed that such actions indicated an “oppositional attitude” and social deviance. He was diagnosed with F91.8 – “other conduct disorders”, which psychiatrists say is the post-Soviet equivalent of the diagnosis “sluggish schizophrenia” once used by the KGB as a tool of punitive psychiatry.

These methods are not confined to the RF territory. In 2024, the security forces of the so-called “DPR” publicly reported prosecuting 161 minors as “radicals”, 48 of whom were forcibly sent for psychiatric treatment.

This confirms that psychiatric coercion is increasingly being used not for treatment, but to suppress dissent – even among children.

Labelling minors as “terrorists” or “extremists” in Russia and in the TOT is not an attempt to counter real threats, but part of a policy of intimidation. Particularly dangerous is the growing use of psychiatric measures as a tool of “disciplinary terror” – to show other children and families that even the smallest act of resistance or symbolic defiance can lead not only to prosecution but also to confinement in a psychiatric hospital.

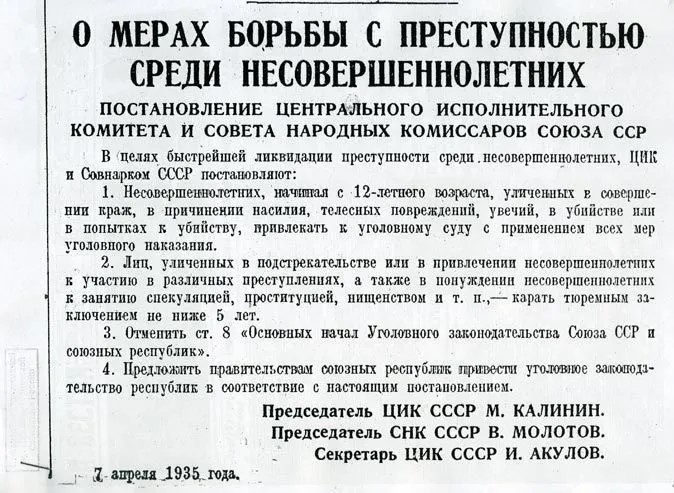

This logic is nothing new. As far back as 1935, the USSR adopted a decree allowing children from the age of 12 to be held criminally liable, including facing execution. The most well-known case is that of Volodymyr Vynnychevskyi, who in 1940 was executed at the age of 17 for a series of attacks on children. This exceptional but telling example became a symbol of the Soviet system’s approach to minors. Today, the Russian Federation is reviving this tradition – in new forms and with new technologies of control, but with the same aim: to keep society in submission through fear.

Escalating Persecution

On 25 July 2025, Bill No. 755710-8 was submitted to Russian President Vladimir Putin for signature, introducing amendments to the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation. Under these changes, from September 2025 a new Article 13.53 will take effect, establishing administrative liability for the “deliberate search for extremist materials” online – including through the use of VPNs or other means of bypassing blocks. The penalty is a fine of up to 5,000 roubles. Police officers and Federal Security Service (FSB) personnel will have the authority to draw up reports under this article.

The introduction of this provision effectively legalises prosecution for the mere act of reading information deemed prohibited, regardless of the user’s intentions or the context.

Notably, the bill was initially submitted as a technical initiative in the field of transport security. However, by the second reading, it had been amended to include provisions that significantly restrict citizens’ digital rights. This is a typical tactic of the Russian authorities – disguising tools of repression as formal technical or security amendments to avoid public outcry and broad discussion.

As of late July 2025, the list of prohibited materials published on the website of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation contains 5,475 entries, ranging from religious literature and opposition publications to popular science texts on political topics. Such a large number and the vagueness of the criteria create conditions for arbitrary interpretation and selective prosecution.

At the same time, the Russian Federation has formally established at the regulatory level that any expression of a pro-Ukrainian stance – or even opposition to the war against Ukraine – can be treated as the ideology of terrorism or extremism. These provisions are set out, in particular, in the Comprehensive Plan to Counter the Ideology of Terrorism in the Russian Federation for 2024–2028, approved by Presidential Decree No. Pr-2610 of 30 December 2023, and in the Strategy to Counter Extremism in the Russian Federation, approved by Presidential Decree No. 1124 of 28 December 2024.

The Register as an Instrument of Repression

The expansion of the Register of Terrorists and Extremists – especially through the inclusion of Ukrainian citizens from the temporarily occupied territories – shows the growing use of legal mechanisms to create an atmosphere of fear and submission. Being added to the list is increasingly unrelated to any real threat and instead stems from political or ideological markers, such as holding a pro-Ukrainian stance.

The expansion of the Register of Terrorists and Extremists, particularly through the inclusion of Ukrainian citizens from the temporarily occupied territories, shows the growing use of legal mechanisms to create an atmosphere of fear and submission. Being added to the list is increasingly unrelated to any real threat and instead stems from political or ideological markers, such as holding a pro-Ukrainian stance. The involvement of minors in this process, along with the combination of legal, social and psychiatric measures, indicates an attempt to influence not only the individual but also their family and wider circle, instilling fear. In the context of occupation, such practices create a sense of defencelessness, where any expression of difference can become grounds for punishment.

It is crucial not to leave children in the occupied territories without attention and support, and for international institutions to step up efforts to stop Russia from using so-called “counter-extremism” measures as a tool for persecuting dissent and violating the rights of children in the temporarily occupied territories.

The article was first published in Ukrainian on the website of ZMINA.

Material was prepared by the Center for Civic Education “Almenda” within the framework of the project “Defending Identity: Protecting Ukrainian Children in Occupied Territories”. The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the Public Organization “Center for Civic Education “Almenda” and does not necessarily reflect the position of Civil Rights Defenders.