Cinema as a Tool for Political Indoctrination of Children in the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine

The Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the RF, Russia) is increasingly strengthening its propaganda influence on children and youth in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine (hereinafter referred to as the TOT). For this purpose, the occupying power and their representatives in the occupied territories use a variety of tools that are implemented through formal and non-formal education, youth movements and organizations, and a network of camps.

Read more about some of the propaganda tools in the report CRIMEAN SCENARIO 2.0: HOW THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IS DESTROYING THE UKRAINIAN IDENTITY OF CHILDREN IN THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES.

The UK Ministry of Defense also talks about the tendency to strengthen ideological control, militarization and politicization of the Russian education system in the TOT, noting that texts supporting the so-called ‘special military operation’, anti-Western propaganda, Soviet literature and patriotic (pro-Russian) military papers are increasingly being distributed in schools. As modern conflicts increasingly involve not only armed confrontation but also active information warfare, cinema is becoming one of the most effective tools for shaping the desired political mindset. Young people in the occupied territories are especially vulnerable to this impact. Due to its ability to create strong emotional images, cinema becomes an ideal channel for ideological influence.

The purpose of this article is to analyze the possible impact of film screenings on the minds of children and youth from TOT based on the content of these films.

Psychological impact

Watching cartoons and movies significantly influences young viewers, as children – due to their age and still-developing critical thinking – often perceive the content as true. The authors of the study The Influence of Cinema on the Emotional Aspect of Adolescents’ Personality note:

“Cinema plays a vital role in shaping a teenager’s personality. In particular, it allows them to absorb the life experiences of others, evokes new feelings and emotions, encourages reflection, helps them look at things from a different perspective and think about their own life stance, their ‘life credo’. It gives teenagers an opportunity to live vicariously through various characters, to feel the strength and resources to resolve difficult life situations, to develop empathy, to realize and systematize one’s own life experience.”

In the most vulnerable period of personality formation, cinema actively influences political consciousness through its emotional and figurative means.

Studies by cognitivists, such as J. Piaget and J. Adelson, show that the most intensive formation of political ideas occurs between the ages of 11 and 15. This process has its own stages: at the age of 11-13, there is a rapid development of political thinking, while at the age of 16-18, the dynamics slows down significantly. At the same time, the thinking of 11-year-olds remains specific, personalized and egocentric. For example, when talking about education, they imagine a teacher or a school principal; the mention of the law is associated with a police officer, a criminal, or a court; the concept of “government” evokes the image of a queen, a minister, or a mayor.

At the age of 15, young people are already capable of abstract, formal and logical thinking, which allows them to quickly accumulate political knowledge, assimilate traditional ideological ideas, social conventions and stereotypes. At the same time, it is during this period that the mass media become a leading source of information and an authoritative guide to behavioral patterns. Among all types media, feature films have the most powerful influence on the formation of such models.

Films often present emotionally charged portrayals of heroes and traitors, ‘friends’ and ‘foes’, good and evil, frequently bypassing rational analysis. Due to manipulation of cultural and political stereotypes widespread in the collective consciousness, viewers often instinctively label a character as negative if his or her actions contradict prevailing cultural norms. However, viewers often do not think about whether these events have anything to do with reality. The main power of cinema lies not in narration, but in the visual portrayal of events and ‘exemplary heroes’, which creates a psychological shift from the narrative to modeled behavior.

In addition, the psychological ‘effect of a hero‘ activates the mechanism of empathy: viewers empathize with the character, adopt his or her values and views, even if they did not share them before. And if the messages conveyed in a film are reinforced by current media narratives, a phenomenon known as cognitive consonance occurs, where individuals tend to seek out information in the media and other sources that aligns with their pre-existing ideological beliefs. In this way, cinema does not only serve as a secondary informational backdrop for children and young people; it actively shapes the foundations of their ideological and political patterns.

What are the children in the TOT exposed to?

The screening of films for the TOT children is carried out both as part of formal education: weekly classes “Conversations about Important Things”, events dedicated to the “Year of the Defender of the Fatherland”, screening of educational films, and as part of non-formal education: festivals, competitions, events, in particular the “Victory Cinema” event, during which city cinemas offer free screenings of films about the “Great Patriotic War” to schoolchildren. In order to meet the propaganda targets, Russian educational institutions in the TOT are guided by a clear list of recommended films approved by the senior executives of the Russian Federation.

In March 2025, Russian Education Minister Sergei Kravtsov presented the “List of the Golden Collection of Films” approved by his ministry and recommended for family viewing, as well as for educational organizations as part of their curricular and extracurricular activities. The list contains 408 films organized by age group and thematic category. The analysis of the films on the list shows that the vast majority of topics directly or indirectly relate to wars (World War I and World War II, the war in Afghanistan, the current Russian-Ukrainian war), only 73 of the 408 films, or 18%, were made during the period of Russian independence, and the rest are Soviet-era films.

According to the information about the release year of the films from “List of the Golden Collection of Films”, some films are undated.

Soviet films

The overwhelming majority of Soviet films shown to children in TOT are historical, usually war dramas. The significant influence of ‘visual history’ perceived through film watching is described in scientific papers, in particular in the work of O. L. Kovalkov The Afghan War of the USSR (1979-1989) in Soviet Feature Films in the Context of ‘Visual History’:

“Western historians consider feature films as an important transmitter of historical knowledge, a powerful tool for shaping historical memory, which can also shape and change the political views of society. Historical films help create a sense of involvement in the audience and emotional perception of the past on the screen as realistic. The film tells a story as a fairy tale with a beginning, a climax and an end. The film usually depicts an episode of the past as a story of individuals – characters who found themselves in certain historical circumstances. The film emotionalizes, personalizes, and dramatizes history. It gives us history as triumph, anguish, joy, despair, adventure, and heroism. These emotions are evoked in a variety of ways: close-ups, quick juxtaposition of disparate images, the power of music and sound effects. This creates the effect of involvement in what is happening on the screen. This way, the film complements our understanding of the past prompting us to internalize and emotionally engage with historical events.”

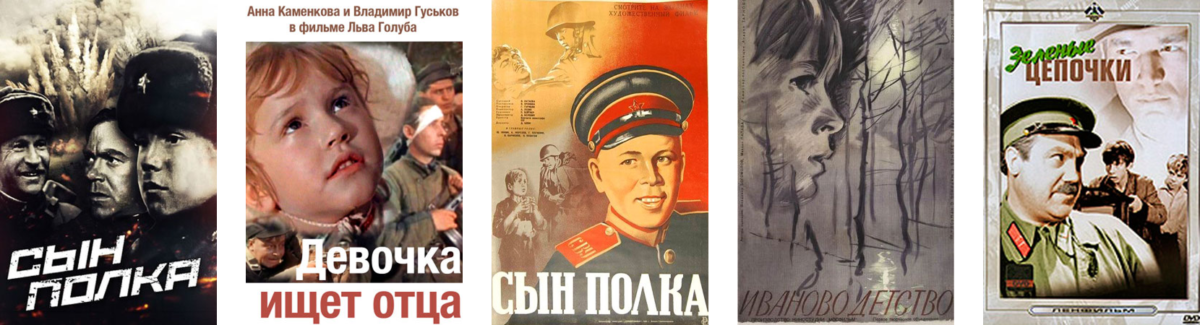

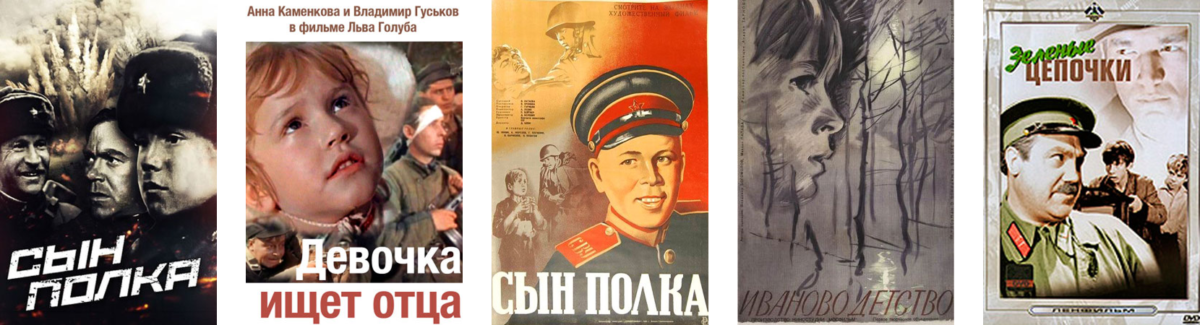

Many Soviet films (from the list of films recommended by the Russian Ministry of Education) that are positioned as historical films have a protagonist who participates in the war in one role or another, and is portrayed as courageous, brave, ready for self-sacrifice, and evoking emotions of admiration and/or sympathy. Often, this character is a child, approximately the same age as the young viewer (the films Son of a Regiment, Green Chains, Ivan’s Childhood, A Girl Looking for a Father, Goodbye Boys, etc.).

It is important to note that Soviet films from the 1930s and 1940s onwards associate military action with (social) liberation, particularly when such action is carried out by the Soviet Union. In later films, the army becomes the main instrument of liberation, which is understood as overcoming ethno-national conflict by invading a certain ethnic territory. It is no coincidence that the Russian authorities use such plots to show children, aiming to influence the children’s psyche, which perceives what they see on the screen as a real story, empathizes with the characters and strives to be like them – a defender of their ‘land’ and their ‘homeland’.

War and Nationalism in Soviet Cinema (1927-1941) by Yakiv Yakovenko Spilne, No.10, 2016: War and Nationalism.

Contemporary Russian films

It is worth noting that children are shown not only the Soviet legacy, but also contemporary Russian ‘historical’ and ‘documentary’ films. Although their number is significantly smaller compared to the Soviet legacy, their propagandistic content deserves special attention in view of the use of tools of falsification, rewriting history, incitement to ethnic hatred, discrimination, and other tools to justify Russia’s aggressive policy.

These films include the propaganda series Myths about Russia based on a book by Vladimir Medinsky, Aide to the President of the Russian Federation. In one of the episodes, the authors ‘manage’ to prove that Russia has never attacked other nations, and that the annexation of territories, such as Siberia, was not through wars, but through ‘incorporation’. Vladimir Medinsky also published history textbooks for grades 10-11, which are the only source of studying history in the TOT.

For more information on textbooks authored by V. Medinsky, see materials of the Almenda Centre of Civil Education:

- Research into the Content of Russian School Textbooks (2014-2022)

- Why Russia’s Unified History Textbook Violates International Law or a New Dimension of Propaganda in the Occupied Territories

Another striking example of contemporary Russian documentary shown to children is the film Operation Ukraine: Bandera’s Dark Shadow (2023). This film contains footage of violence, fighting, and killed people, which are interpreted as ‘footage of the atrocities of the Ukrainian nationalists of Azov’. The film depicts a distorted life story of Stepan Bandera, calling him the leader of ‘nationalist units of the Ukrainian SSR, which operated during and after the Great Patriotic War and were supported first by the Wehrmacht and then by the CIA, fighting the Soviet government, killing civilians’. Parallels are drawn between the children’s organization Plast and the Nazi paramilitary organization Hitler Youth, imposing the claim that the goal of the Plast was ‘to confront the Orthodox Russian-speaking majority of the population in western Ukraine with armed force’. In the film, the so-called experts call the members of the Right Sector and Azov, who allegedly use the regime against Russia, modern-day followers and ‘neo-Nazis’, which is why ‘they are deliberately prolonging the special military operation, while the West continues to supply them with weapons’. The authors conclude that ‘the Nazis, Banderites and the US are in the same boat against Russia, and the EU is a prototype of Hitler’s coalition’. The narratives used by Russian propaganda are aimed at creating an image of the enemies – Ukraine and the ‘collective West’ – in the minds of viewers, forming an obsessive awareness of the need to fight them, in particular through active participation in wars.

One of the films recommended for students in grades 10-11 is Call Sign ‘Passenger’ (2024), which depicts the events of 2015 in Donbas during the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The film is filled with Russian propaganda aimed at fostering a dismissive attitude toward the Ukrainian military, portraying them as criminals and supporters of Nazism, and features a shot of a dead Ukrainian soldier with a swastika. The film features the image of a boy who is interested in Russian literature. The culmination of the storyline with the boy is the moment when he steps out onto the road in front of a Ukrainian tank, holding a Soviet flag, with portraits of Pushkin and Gogol hanging on his chest and back like a bulletproof vest. The child refuses to move out of the way and the Ukrainian soldier shoots him. The Russian state budget allocated RUB 246.2 million for this propaganda ‘masterpiece’. Such films are aimed at justifying Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Another propaganda documentary is Aldan, which is scheduled to premiere in Russia on May 1, 2025. The film depicts the events of the war in Ukraine, namely in the Zaporizhzhia Region, where a Yakut programmer goes to fight, calling the occupied territories of Ukraine the territory of Russia. The film shows the image of a Ukrainian soldier talking about the sale of bodies for organs, including children’s bodies. It is noteworthy that the so-called governor of Zaporizhzhia Region Yevhen Balytskyi and the governor of Yakutia Aysen Nikolayev starred in the film, and the proceeds from the film will be used to support the so-called special military operation.

Influencing children’s consciousness through the images in films is one of the elements for the gradual Russification and preparation of Ukrainian children for life in the Russian context. By using the substitution of concepts in films, when the occupiers are presented as defenders and the victim is blamed for starting the war, the Russian Federation is trying to foster hatred towards Ukraine in Ukrainian children. Instead, the depiction of romanticized military events in films and the heroization of the Russian military helps to form a positive attitude toward war in children.

Distribution in the temporarily occupied territories

Based on the Soviet experience, the RF is expanding the practice of using cinema for propaganda purposes to the TOT. The first region where Russian films were shown to children in the first years of occupation was the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol. And with the occupation of new territories, the practice of influencing children and youth was extended to these territories; and the occupying authorities began to force them to attend such screenings.

Features of the Organization and Adaptation of Film Propaganda to Target Audiences in the Ukrainian SSR (1943-1945) Dmytro Viedienieiev

During these events for schoolchildren from various educational institutions of the TOT of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol:

- As part of the Victory Cinema Campaign, they showed the Soviet film Belorussian Station about a meeting of former military 25 years after the end of the war, which uses the song We Need One Victory. The song calls for the continuation of the war at any cost, and it is also widely used by the Russian Federation in its propaganda campaigns. The Victory Cinema Campaign also includes screenings of other similar Soviet films, such as The Dawns Here Are Quiet, The Cranes Are Flying, Officers, Belorussian Station, as well as contemporary films such as The Battle of Sevastopol and Panfilov’s Twenty-Eight Guardsmen, which are aimed at creating a romanticized image of war in young viewers and encouraging them to realize the need to protect their homeland (i.e. Russia). By the way, Panfilov’s Twenty-Eight Guardsmen was directed by the aforementioned Vladimir Medinsky and depicts a myth invented by Russian propaganda about the feat of 28 soldiers of the 316th Infantry Division under the command of General Ivan Panfilov, who, according to the film, destroyed 18 enemy tanks and died in battle during the enemy’s offensive on Moscow. The deception was revealed in 1947, when one of the soldiers was arrested for treason, who confirmed that the battle had indeed taken place, but that they had not performed any feats and had voluntarily surrendered to the Germans. However, even this historical evidence did not prevent Russian propaganda from using the Soviet myth of the soldiers’ feat.

- Movie Suvorovets 1944 about a 13-year-old Suvorov School student Vovka Kulikov, who is positioned as a role model.

- Movie The Fate of a Man about the events during and after World War II.

- The Russian Society ‘Znanie’ showedhttps://archive.ph/wip/xmSqJ the students of the Crimean Federal University a documentary Our Relatives, which is a propaganda film about the military dynasty of the Bogush-Denysenko family, whose different generations fought on different fronts: from the World War I to the so-called special military operation. By drawing an analogy between the First and Second World Wars and the so-called special military operation, the RF is trying to justify its armed aggression against Ukraine in the eyes of viewers of such films.

- Movie Access Code: The Liberation of Crimea about the justification of the events of the occupation of Crimea has been shown to schoolchildren on the peninsula since 2024.

The following films were screened for the schoolchildren of the TOT in Zaporizhzhia Region:

- A documentary Resilient as part of the project ‘No Statute of Limitations’. The film is part of the propaganda cycle ‘Thank You for Your Service!’ aimed at popularizing service in the Russian security forces and glorifying Russian military personnel.

- Movie Heroes Are Alive was shown to students of school No. 15 of TOT of Melitopol , Yakymivka school No. 27 and Novodniprovsk school of TOT of Vasylivka District with the support of, among others, the Russian propaganda organization ‘Immortal Regiment of Russia’. This organization holds marches of the same name, with portraits and speeches honoring war veterans, which are used as a tool of military propaganda.

- Movie War and Peace for students of Kostiantynivka School No. 2, a series of short films about the war as part of the Movie Break Film Festival for children of Veselivska School No. 52.

The following films were screened for the schoolchildren of the TOT in Kherson Region:

- Movie The Fate of a Man in Henichesk School No. 3 with the participation of a representative of the occupying authorities, the so-called deputy governor Tetiana Kuzmich. The same film was also shown to children of the Hryhorivka School.

- Movie Liberation. Victory Artists about the war events was watched by students of Strohanivka and Hryhorivka Schools.

- The students of Chaplynka Agricultural College saw special TV reports Azovstal: Liberation, whose author notes: “Thanks to the project, the youth of Kherson Region will be able to expand their knowledge of the course of the special military operation, as well as the reunification of Crimea with Russia. It perfectly refutes Ukrainian propaganda.”

In the TOT of Donetsk and Luhansk Regions, children and youth are also actively subjected to forced screenings of Soviet-era and contemporary propaganda films, often scheduled to coincide with Victory Day:

- As part of the all-Russian Film Campaign Victory Cinema!, schoolchildren in the occupied Luhansk Region had to watch the film Belorussian Station.

- A Soviet film about the war The Fate of a Man was shown to children of the TOT of Donetsk Region. On the same territory, films about Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine were also screened: Chronicles of the SMO. Monologues, Sit Down, Soldier, which justify Russian aggression.

- Movie Little Soldier, which tells the story of six-year-old Serhii Aloshkov, who took part in the battles for Stalingrad during World War II. The choice of audience’s age was far from accidental: children in grades 1 through 5 from Nevska School and School No. 27 in the occupied Donetsk Region were targeted deliberately. Seeing peers on screen and a storyline centered on heroic deeds is intended to inspire these children to use them as role models.

Russia is actively using cinema in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine as a tool of disinformation and manipulation of the minds of children and young people. The screening of Soviet-era and contemporary films that distort historical events, justify aggression, and impose the image of a ‘heroic liberator’ is part of the Kremlin’s broader information warfare strategy.

As stated in the European Parliament’s Resolution on Russia’s disinformation and historical falsification to justify its war of aggression against Ukraine (2024/2988(RSP)), Russia systematically falsifies history by denying the role of the USSR in the outbreak of World War II (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) and using ‘victorious’ rhetoric to mobilize the population. Such distortions, including the mythologization of Victory Day, are turning into a powerful tool to justify the current criminal aggression against Ukraine and attempts to destroy Ukrainian identity.

Through forced screenings of films, as well as in the context of insufficiently formed critical thinking among children, the occupying authorities seek to eradicate children’s Ukrainian identity, form loyalty to the occupying regime, hostility to Ukraine and the West, and justify the war as a ‘sacred mission’. Counteracting these actions requires not only military struggle, but also an active information policy aimed at protecting the truth, developing critical thinking, and supporting Ukrainian national consciousness among young people.

This article was prepared with the financial support of the Czech organisation People in Need, as part of the SOS Ukraine initiative. The contents of the publication do not necessarily reflect their position.